|

Appendix B: A Review of the Health and Disability Commissioner’s Opinions about Capacity

Introduction

- This is a review of the Health and Disability Commissioner (Commissioner) opinions and Human Rights Review Tribunal (HRRT) decisions.1 It shows that over time, the issue of whether a person (consumer) lacks capacity or is vulnerable due to impaired capacity for decision-making, even where there may already be a decision-maker appointed, has become significantly more relevant in the complaints investigated by the Commissioner.2 There is a greater emphasis on ensuring that providers of health and disability services (providers) adequately assess capacity, and that they are clear about the legal basis on which substitute decisions are made when a person cannot give informed consent. Substitute decisions are legally valid when they are made by a welfare guardian, an attorney under a properly activated enduring power of attorney (EPOA), or by the provider under Right 7(4) of the Code of Health and Disability Services Consumers’ Rights (HDC Code) if an assessment is made that the decision to provide care and treatment is in the person’s best interests.

- When the Commissioner finds a breach of the HDC Code, there are three possible outcomes that may follow: firstly, making recommendations to the provider; secondly, reporting the Commissioner’s opinion to other “appropriate persons”; and thirdly, referring the provider to the Director of Proceedings to decide whether to institute disciplinary and/or compensation proceedings in the HRRT.3

Method

- This review evaluates opinions of the Commissioner published on the Health and Disability Commissioner’s (HDC) website.4 It covers opinions from 1997 to 2015.5 These opinions were reviewed to assess whether the Commissioner found the issue of capacity for decision-making relevant to a breach of the HDC Code or an adverse finding. Twenty-eight opinions were analysed in-depth. It is relevant to note that only complaints that result in a formal opinion by the Commissioner are published on the HDC website, and this is, on average, less than 10 percent of complaints actually lodged with the HDC.6

- In addition, eight decisions of the Human Rights Review Tribunal (HRRT), relating to seven matters, were found for the period 2002 to 2015.7

- While this review does look at a limited number of cases where a person is vulnerable due to impaired capacity, it is not a review of the broader aspects of vulnerable adults – whether they have capacity or not.

Health and Disability Commissioner complaint process

- The functions of the Health and Disability Commissioner are set out in the Health and Disability Commissioner Act 1994.8 The Commissioner acts as the initial recipient of complaints about providers of healthcare and disability services and is required to ensure that each complaint is dealt with appropriately.9 He is also responsible for investigating, either upon receiving a complaint or upon his own initiative, any action that appears to be a breach of the HDC Code.10

- The Commissioner has the discretion to refer cases to the Director of Proceedings, to consider initiating further action, but this occurs in only a limited number of cases where a breach has been found.11 Even fewer cases are actually referred for further action, whether to the HRRT, or the Health Practitioners Disciplinary Tribunal (HPDT).12 This gatekeeping means that the resulting pool of potential cases before the HRRT is very small.13

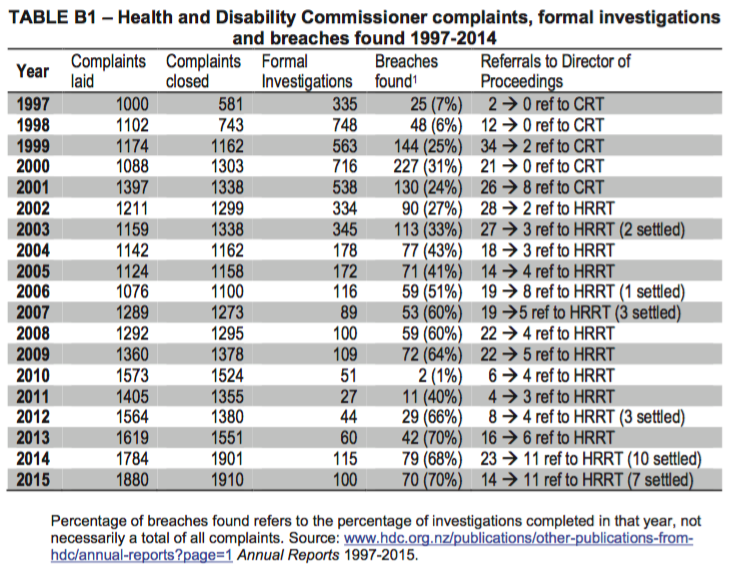

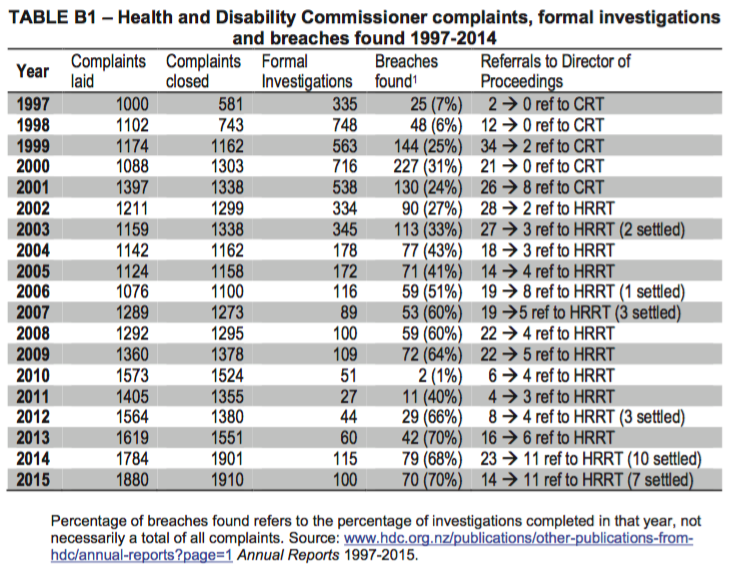

- Table B1 shows that only a small proportion of complaints made to the Commissioner lead to a formal investigation. On receipt of a complaint, the Commissioner has a range of options to choose from.14 Where the Commissioner considers more information is necessary to assess the complaint, it will be sought from the complainant, the provider, in- house clinical and nursing advisors, and occasionally external experts. On the basis of this information, the Commissioner can refer the complaint back to the provider or agency;15 to an advocate;16 call a conference of the parties concerned for formal mediation;17 launch a ormal investigation;18 or take no further action.19 Once the Commissioner has compiled all the relevant information, a provisional opinion is issued, which both the consumer and the provider may review and respond to. The report is then finalised and the Commissioner may make a recommendation, ranging from the making of a formal apology to specific recommendations on how the provider could improve services.20

- The number of formal investigations undertaken annually has decreased from a high of 748 in 1998 to an average of 57 each year for the past five years.21 Breaches of the HDC Code were found in about 60% of opinions, although this number has risen slightly in the past three years.

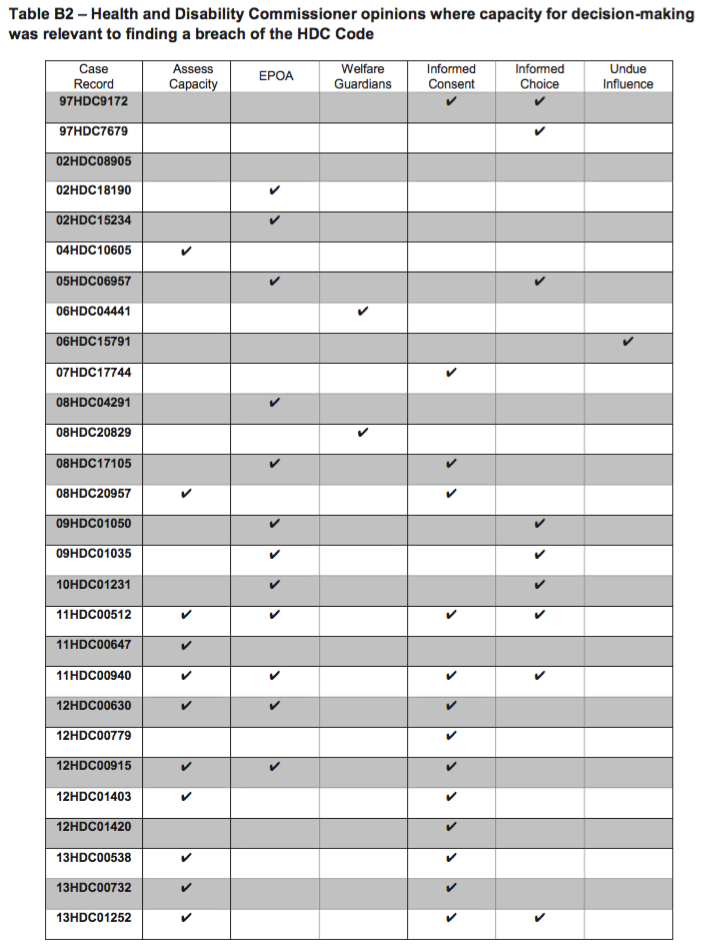

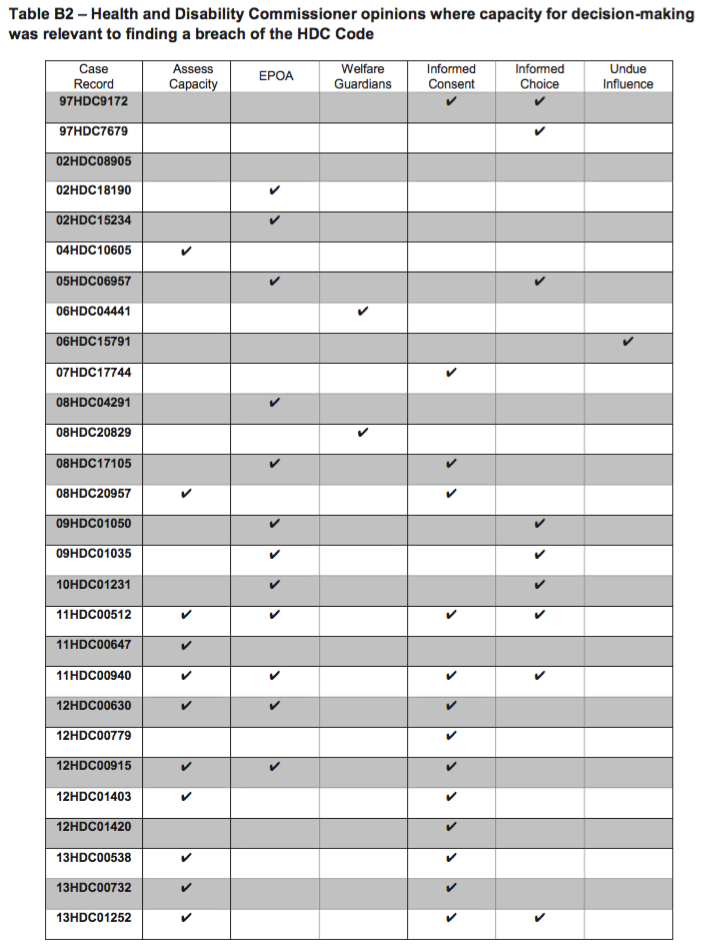

- Table B2 shows opinions where capacity for decision-making was relevant to a finding of breach of the HDC Code.

- The majority of these opinions concerned findings of a breach of Right 4, the right to services of an appropriate standard; and/or Right 6, the right to be fully informed; or Right 7, the right to make an informed choice and give informed consent. Almost half of the cases in this review concerned breaches of the Code in relation to EPOAs and related to either the process of assessing capacity and/or whether informed consent had been properly obtained. The capacity issues concerned:

-

assessing capacity, including failure to determine competence or adequately assess competence;

- enduring powers of attorney (EPOA), including an EPOA not being properly activated, inadequate communication from the healthcare provider to the attorney, and multiple attorneys for personal health and welfare decision;22

- welfare guardians, including the welfare guardian not being adequately consulted, and the welfare guardian failing to fulfil their duties;

- informed consent (Right 7), including lack of consent, consent given with no legal authority, and Right 7(4) being applicable but not relied upon by the healthcare provider;

- informed choice and information disclosure (Right 6), including failure to ensure an informed choice was made and failure to keep the family informed; and

- undue influence where the person had impaired capacity and undue influence was exerted.

a) Failure to undertake a capacity assessment

- In 11 of the cases reviewed the (lack of) assessment of capacity was directly at issue. In General Surgeon (2014),23 the patient’s wife signed a consent form for a surgical procedure.24 The Commissioner made an adverse comment that:25

There was no evidence that Mrs A was Mr A’s legal representative, nor is there any clear record of any assessment of Mr A’s competence to consent on his own behalf.

- Similarly, in Waitemata DHB (2015)26 the Commissioner made an adverse comment against the District Health Board (DHB). The patient was an elderly man who had arrived in hospital by ambulance, conscious but confused. Evidence showed that the anaesthesia consent form was signed by one daughter, and the consent to surgery was signed by a second daughter. There was no record of any assessment of capacity to consent, and neither daughter had any legal right to consent on their father’s behalf.

- In both these opinions, the Commissioner observed that, in the circumstances, the relevant health practitioners could have proceeded with treatment in the absence of the consumer being able to consent, if it was in the consumer’s best interests, under Right 7(4) of the Code. Concern was expressed about the DHB lacking understanding of the legal requirements for consent where the consumer was incompetent to consent and there was no legally authorised substitute decision maker.27

- In Dr C (2013), a General Practitioner (GP) failed to assess a patient over a ten-year period, even though she knew the woman had Huntington’s disease.28 The patient’s psychiatrist had recorded suspected dementia in 1997. Beginning in 2001, Dr C made home visits to Mrs A and was aware of her deteriorating condition, but promised to help her live at home as she was strongly opposed to institutionalisation. Between 2006 and 2010, the GP had contact with Mrs A only on the telephone or through a curtained door. Mrs A became reclusive and refused home help and support, living in circumstances described as “extreme squalor”. The Commissioner opined that Dr C had breached Right 4(1) of the Code:29

Given the known trajectory of patients with HD and the probability that Mrs A would at some stage lose competence, Dr C’s failure to assess Mrs A’s competence to make the relevant decision was suboptimal care and unacceptable.

b) Enduring powers of attorney (EPOAs)

- In many cases where there has been an issue regarding an EPOA, the focus is on whether it has been properly activated. Section 98(3)(a) of the PPPR Act requires certification by either a relevant health practitioner or the court before the attorney can act in a significant matter relating to the donor’s personal care and welfare.

- A “significant matter” is defined in the legislation as being “a matter that has, or is likely to have, a significant effect on the health, wellbeing, or enjoyment of life of the donor, for example, a permanent change in the donor’s residence, entering residential care, or undergoing a major medical procedure”.30 The New Zealand Law Society has highlighted the lack of independent oversight of the medical certification process required to certify a donor’s mental incapacity.31

- In Ross Home and Hospital (2010), a wife had been appointed as care and welfare attorney under an EPOA for her husband who was in a dementia unit.32 The Deputy Commissioner opined that the EPOA had not been activated because Mr A’s mental incapacity was not certified as required by the PPPR Act. The rest home was found to be in breach of Right 4(1) for failing to ensure that Mr A’s condition was assessed and evaluated effectively.

- In Killarney Rest Home (2013),33 an 81-year old woman with advanced dementia was admitted to a secure dementia unit for short-term respite care. Nurse D advised the Commissioner that she had completed an admission assessment and care plan, although no records were found. The records stated that Mrs A’s son-in-law was her attorney under an EPOA, but no copy of the document or evidence of its activation was found in Mrs A’s records. The Deputy Commissioner opined that the rest home and the nurse were in breach of Right 4(1) for multiple reasons, including failure to clarify or document an EPOA, and for failing to inform the attorney or family of Mrs A’s falls which resulted in her being left untreated with a fractured pelvis for five days, despite believing there was a valid EPOA. The matter was referred to the HRRT, which determined that Killarney failed to communicate effectively with Mrs A’s family and power of attorney, and there was a breach of Rights 4(1) and 4(2) of the HDC Code.34

- The appointment of multiple attorneys, despite restrictions in the PPPR Act limiting an attorney for care and welfare to one individual, can also cause problems.35 In Villa Gardens (2009),36 an elderly woman with dementia had jointly appointed two of her four daughters as her attorneys under a care and welfare EPOA. One daughter was nominated as first contact, yet all four daughters were involved in making contradictory decisions regarding their mother’s care. The Deputy Commissioner opined that there was a breach of Right 4(1) as Villa Gardens had taken “no steps ... to resolve who the attorney was”.37 The care manager should have known that the PPPR Act “provides that an EPA (sic) may not appoint more than one person as attorney”.38

- There can also be an issue of how to “de-activate” an EPOA after a person has been certified mentally incapable, but subsequently regains capacity for decision-making. In Canterbury District Health Board (2013),39 Mrs A had a complex medical history including suspected dementia. Mrs A’s daughter appointed her daughter as her attorney under an EPOA, but it had not been activated in the required manner. When Mrs A was admitted to hospital with a diagnosis of pneumonia, she was delirious and haloperidol was prescribed. The Deputy Commissioner found the DHB was in breach of Right 7(1) as the clinicians should not have administered haloperidol unless they had a legal basis to do so, either through Right 7(4) of the HDC Code or through activation of her EPOA if Mrs A was not competent to consent to its administration due to delirium.40 The opinion cited a senior DHB clinician as stating that one-third of all patients over 65 years old in an acute clinical setting will present with delirium, which by its very nature is transient and variable.41 One of the Commissioner’s recommendations was for the DHB to provide guidelines on consent in such cases where a patient’s ability to consent may fluctuate due to delirium.42

c) Welfare guardians

- As with EPOAs, the role of welfare guardians is to protect and promote the welfare and best interests of the subject person.43 Even when families go to considerable trouble to have a welfare guardian appointed, there is no guarantee that the welfare guardian will then be consulted by health care providers.

- In Nilsson v Summerset Care Ltd (2012),44 Mrs A was a frail, elderly woman with pneumonia discharged from hospital to a Summerset rest home. The hospital discharge summary instructed the caregivers at Summerset to closely monitor Mrs A’s fluid intake and hydration. Four days after her admission, Mrs A’s daughter and welfare guardian informed the staff nurse of her mother’s deteriorating condition and requested that her mother be seen by a GP, but was told this would not occur for another four days, on the GP’s regular weekly visit. Mrs A died two days later. The Commissioner found that Summerset Care Ltd and the nurse manager were in breach of Right 4 for failing to provide services of an appropriate standard, particularly by not obtaining medical intervention in a timely manner; and in breach of Right 6 for failing to consult and inform Mrs A’s welfare guardian of her mother’s deteriorating condition, or of treatment decisions. Proceedings were issued and settled in the HRRT, including a compensatory sum.45

- Spectrum Care Trust (2007),46 concerned a 45-year old man who had been in care since the age of three and had a welfare guardian since 1995. The Commissioner opined that the caregiver breached Rights 1, 3 and 4 of the Code with regard to his care. The Commissioner commented:47

... I am disappointed that Spectrum Care did not seek assistance or support from Mr A’s

welfare guardian, Mr McEvoy. This shows serious lack of judgement and lack of willingness to work with Mr McEvoy to provide Mr A the best care possible in the circumstances.

- At times, failure by welfare guardians to adequately fulfil their duties – in conjunction with a care agency’s failure to keep them informed – can lead to serious abuse of vulnerable adults. In the case of Registered Nurse Mr B (2004),48 an elderly woman with deteriorating dementia and severely reduced physical mobility was being cared for by a nursing agency in her own home. She had a welfare guardian and two property managers who arranged for the nursing agency to provide two full-time caregivers at all times. Subsequently, staffing levels were reduced as a cost-saving measure. An aged care nursing expert commissioned by the Commissioner to comment on the case stated that:49

Mrs A was subjected to a severe form of abuse and neglect .... The court order gave the Welfare Guardian the power to make all decisions on [Mrs A’s] behalf and the responsibility to ensure she was cared for at the level required either in her own home or in private hospital or rest home care. Instead [Mrs A’s] care was compromised when a decision was made by [the nursing agency], [Mr J] and [Mr I] to reduce the staffing levels below the level she required for her safety and well being. [Mrs A’s] nutritional needs were not considered and her dramatic weight loss was not followed up by her welfare guardian, the nursing agency or her GP. On the development of pressure areas, Mrs A received wholly inadequate care....

d) Informed consent

- Capacity is an essential component of informed consent. Many of the opinions that discuss informed consent were concerned with the failure to conduct an adequate assessment of capacity and/or consent being sought from persons not legally entitled to consent.50 In some circumstances, however, there were more fundamental breaches of the requirement for informed consent.

- In Taikura Trust, 51 Ms A, a 43-year old woman with a complex history of mental illness and alcohol abuse, was held in a secure dementia unit for almost a year, against her will, without legal authority. Although she had initially been appropriately admitted to hospital, having been assessed as not having the capacity to make decisions relating to her care and welfare, the hospital incorrectly assumed an application for a personal order under the PPPR Act had been obtained from the Court. Despite expressing a wish for a more suitable placement, she was effectively detained for over a year in a situation that was not in accord with her wishes or needs. In the absence of any oversight of a Court order there was no reassessment of the woman’s changing capacity over time.

- Although Right 7(4) was a defence for the initial admission to the hospital, it was not specifically relied upon. The Health and Disability Commissioner found there was a failure to provide Ms A with appropriate care under Right 4. Even if a personal order to place Ms A in the dementia unit of Oak Park had been in place, the health care providers did not take the steps to reassess Ms A’s capacity and address the fact that she was inappropriately placed in a dementia unit. The case went to the HRRT where the two Auckland health and disability service providers agreed to pay compensation to the estate of the woman, who had subsequently died after release from her unlawful detention.52 The Tribunal made declarations that the providers had failed to provide services in a manner that respected her dignity and independence and failed to provide services with reasonable care and skill.

- In The Retirement Centre (2002),53 the Commissioner opined that Mr A had been admitted to a rest home against his will, without informed consent, and the Centre had accepted his daughter acting as decision-maker for him when she had no valid authority to do so. It was clear that Mr A had capacity to make decisions in his own right. Mr A was taken for a “drive” against his wishes shortly after the death of his second wife and brought to the Centre. The admittance forms were signed by his daughter. Mr A subsequently left the Centre and paid a portion of the fees that were demanded, but refused to pay for further charges added. Mr A’s solicitor advised the Centre that Mr A accepted no liability for the sum as he claimed the Centre knew he had been brought there involuntarily.

- The Retirement Centre was found to have breached Rights 6(2) and 7(1) for failing to obtain informed consent and failure to provide all the relevant information to the appropriate decision-maker. When the Retirement Centre suggested that Mr A should be liable for all costs associated with his stay at the Centre, the Commissioner clarified that relevant information is required to be voluntarily disclosed to the consumer.

e) Right 6 and information disclosure

- In some cases, a breach of Right 6, concerning the right to make an informed choice, is associated with a failure to assess whether a patient is competent, with the result that decision-making is entrusted to someone without legal authority. An example is when no assessment is undertaken prior to a provider acting on the apparent authority of an EPOA. In Manis Aged Care Ltd (2015),54 healthcare staff failed to ensure that a 96-year old man, who had not been assessed for competence, received relevant information regarding his condition. His own GP had prescribed him antibiotics on a Wednesday. Two days later his condition worsened, but he was not considered terminally ill. Over the weekend, nursing staff advised the doctor on call that Mr A was receiving “end of life” care and the doctor prescribed morphine over the phone. The healthcare staff decided to stop administering amoxicillin, and began administering morphine in accord with palliative care, without getting his consent. Mr A died on the Sunday. The Commissioner found that there was a breach of Rights 6(1) and 7(1) for failure to obtain informed consent, and a breach of Right 4(5) for failure to ensure continuity of services.

f) Undue influence and impaired capacity

- Adults with impaired capacity for decision-making can be especially susceptible to undue influence. The following two examples demonstrate the breadth of situations where caregivers can exploit vulnerable adults who lack capacity in their care.

- In Caregiver H, disability support worker Mr H was found to have breached Rights 2, 3, and 4(2) with regard to his relationship with an 18-year old client, Mr B, who had been assessed as having the capacity of a “10-year old boy”.55 Mr B was in an independent flatting situation. Mr H was a caregiver that Mr B knew from church, and believed to be a friend. The caregiver introduced “sexual elements” to games that they would play and failed to maintain professional boundaries in his relationship with Mr B. In his opinion, the Commissioner stated that:56

Mr H used the caregiver-client relationship as an opportunity to sexually exploit Mr B. A power imbalance existed between Mr H, as a caregiver, and his client, Mr B. Mr B was in a vulnerable position. ... Mr H took full advantage of Mr B’s vulnerability, knowing of Mr B’s impairment.

- Proceedings before the HRRT found that the caregiver’s conduct had breached Rights 1, 2, 3 and 4 of the Code and awarded compensatory damages of $20,000. The Tribunal also agreed that exemplary damages of $10,000 were appropriate, particularly due to A’s extreme vulnerability and the abuse of Mr B’s trust.57

- In Director of Proceedings v Nikau (2010),58 the complainant, Ms A, had a long history of depression and bipolar affective disorders and received respite care and support from a community health coordinator.59 The HRRT held that Ms Nikau, a community health co- ordinator, had “obviously” breached Right 2 of the HDC Code by taking advantage of her position as a caregiver to enrich herself at the Ms A’s expense. Evidence at the hearing established that the complainant had given Ms Nikau money and goods in excess of $40,000. The Tribunal also found Ms Nikau had breached Right 4(2) of the Code for unethical abuse of the relationship with a client for personal financial gain. The Tribunal awarded compensatory damages of $50,000, damages for emotional harm of $30,000, and exemplary damages for “flagrant disregard of the complainant’s rights under the Code” of

$20,000.

Summary

- This review shows that 28 of the Commissioner’s published opinions since 2009 have concerned a breach of the HDC Code related to a person’s impaired capacity to consent to, or refuse, decisions concerning their healthcare. Over time, the issue of whether a person lacks capacity or has impaired capacity for decision-making is becoming more prevalent in the complaints investigated by the Commissioner. Even where there is a substitute decision-maker appointed, there have been breaches of Rights 6 and 7 of the HDC Code in circumstances where the person is unable to make an informed choice or give informed consent. These breaches have occurred when there has been a failure by the provider to determine or adequately assess capacity, or when there has been a failure to properly activate an EPOA, or to consult with the legally appointed substitute decision-maker.

- The Commissioner’s opinions and decisions of the HRRT highlight the importance of having systems in place to ensure a person’s capacity is assessed when there are doubts about a person’s capacity to give or refuse consent to care and treatment decisions; that capacity assessments are clearly understood and implemented by all providers involved with a person’s care; and, the importance of attorneys and welfare guardians being involved in the decision-making process.

|